Sunday Story: RECIPE Shorthand

No recipe today. Instead, a short story.

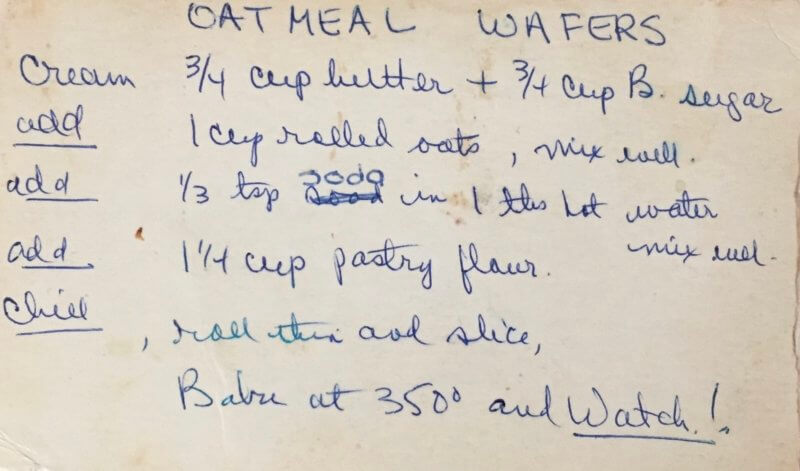

My mother’s recipe box is a colour-coded, multi-tabbed wonder.

Before the Internet coughed up recipes on demand, family, friends and virtual strangers often asked if she shared her recipes. While some people’s were closely guarded secrets handed down through the execution of wills, Mom gave hers freely, with almost evangelical enthusiasm.

“There are far too many bad recipes in the world,” she’d say as she copied out an ingredient list in her neat, all-caps printing. “It’s my duty to share the good ones.” Her intent: to reset the balance, one handwritten recipe at a time.

When my mother transcribed a recipe, her sole aim was to get all instructions on the front of the card. Victory was hers if the recipient didn’t have to flip the card over. To do this, she developed a form of personal shorthand. BS was either baking soda or brown sugar, which the reader would glean from the quantity. Only an idiot would assume her chocolate cookies needed 1/2 cup baking soda. I have been that idiot. Once.

Providing you weren’t a scatter-brained eight-year-old, everything you needed was there. You just needed to know how to decode it. She assumed you’d preheat the oven. She assumed you knew how to butter and flour the cake pan, or which baking sheets to pull from the cupboard. You knew which oven rack to use and when a glass Pyrex baking dish was better than a metal one.

When she wrote “cream the butter” she assumed you knew this involved elbow grease, not whipping cream. When she told you to drop cookies by “small spoon”, she meant HER small spoon. The one used for cookies. It was kept in the baking drawer, not with the rest of the cutlery because it was for cookies, not tea. Everybody knew that, even Dad, who was allowed near the stove only to change fuses and plug in the kettle. Spoons in the baking drawer were not for use at the table. Even at my most idiotic I knew that like I knew my own address.

The only trick to reading one of her recipes was knowing the top, right-hand corner was reserved for oven temperature and baking time. It was easy to miss

350°

12 mins

That was all you got. No spacing, no cookie size, no final yield. Such details were too obvious to state.

My mother was not alone in her assumptions. My friend Sheila’s grandmother told her to mix the pie dough “until it felt right.” Looks, textures, temperatures were measured by the touch of well-seasoned fingers. These hands were taught young, practiced often. I’m sure a bit was passed on via DNA as pregnant mothers baked batch after batch of pies and breads and cakes.

Modern bakers will tell you it’s about precision. Their ovens are calibrated to a tenth of a degree, they use baking stones and weigh flour to the gram. “Close enough” is not in their vocabulary. They swear up and down, shaking a whisk at you for emphasis, that baking is more science than art. You can’t muck about. Woe unto those who veer from the recipe. It’s all chemicals and reactions and delicate balances. I’ll grant you, baking is more precise than cooking a stew or roasting a chicken. But unlike nuclear fission, a misstep or two isn’t going to kill anyone. You might even discover a new dish, a better texture, a more flavourful result.

I’ve gobbled moist chocolate cakes topped with makeshift icing. I’ve left a trail of sweet crumbs from cookies mom invented on the fly when the cupboard was more bare than she remembered. She understood enough about baking chemistry to make sure the bread rose properly and enough about food and flavours to improvise. Her only monumental failure was slipping liver into spaghetti sauce, and even then I’m sure she knew it wouldn’t work but was out of options.

So, pick up a family recipe. Read it. Do your best to follow it and see what happens.

Consistency is wonderfully comforting. Experimentation is wonderfully freeing.

With this in mind, I invite you to do both.